Class 4 started out with a tour of my teacher’s on-site Paulownia storage and his workshop. He ages his Paulownia the traditional way, storing it outside for between 3 to 5 years, which stabilizes the wood physically, chemically, and aesthetically in ways that modern kilns can’t replicate. Below are some images of his stock, already 3+ years aged and ready for use.

My teacher’s workshop is small, organized, efficient. He has a traditionally laid-out corner of the shop adjacent to a modern section with some standard machines for milling larger stock, all well thought-out for workflow. He demonstrated with amazing speed and grace how to hand miter edges on his shooting board using one of his well-honed kana (Japanese pull-plane). What he accomplished in 5 minutes with perfect precision would take us an hour or more!

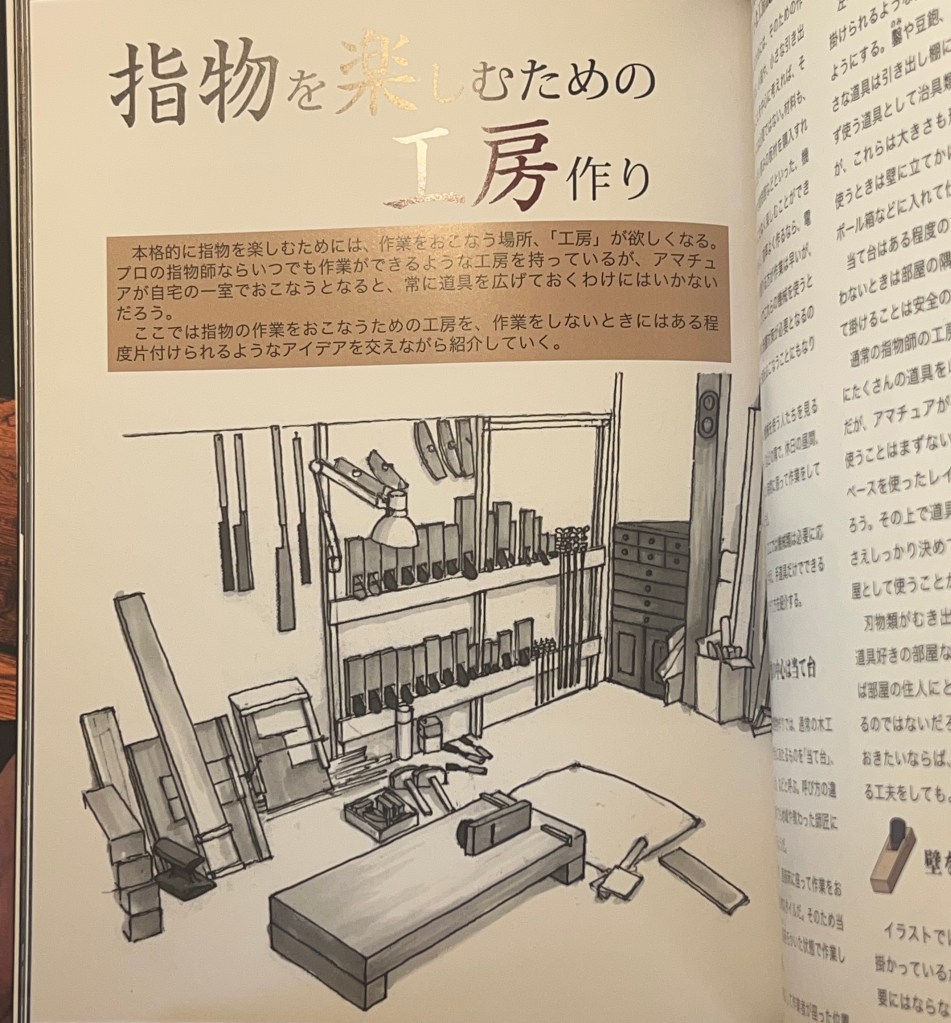

I found this old sketch of a traditional workshop in the library, notice any similarities?

Many Japanese woodworkers used to work on the ground like this. They would often use the strength of their feet and body weight to hold things in place, not unlike how some traditional oolong producers would use their feet, especially the heals, at certain stages of rolling to shape the tea leaves within mesh bags.

Hyodo sensei is definitely preserving the tradition of this Kyoto-style sashimono as can be seen in the design of his shop, the way in which he works himself, and teaches students like us. It’s a very honorable way of life for him and I find my self endlessly grateful for his experience, wisdom, and guidance in this apprenticeship.

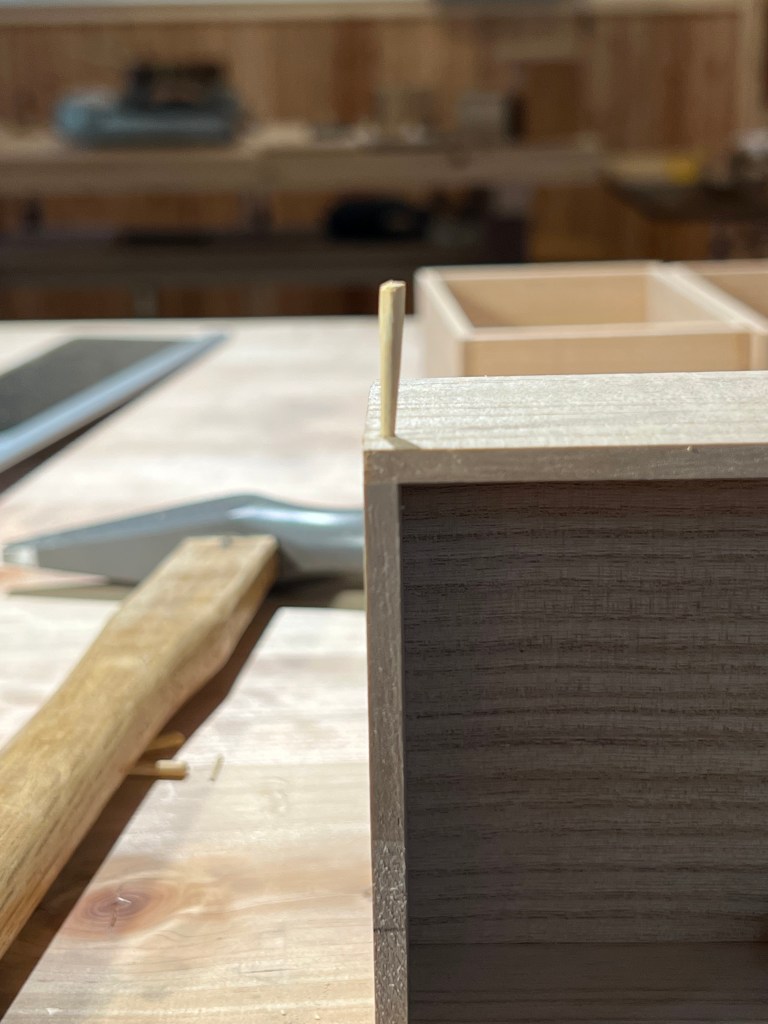

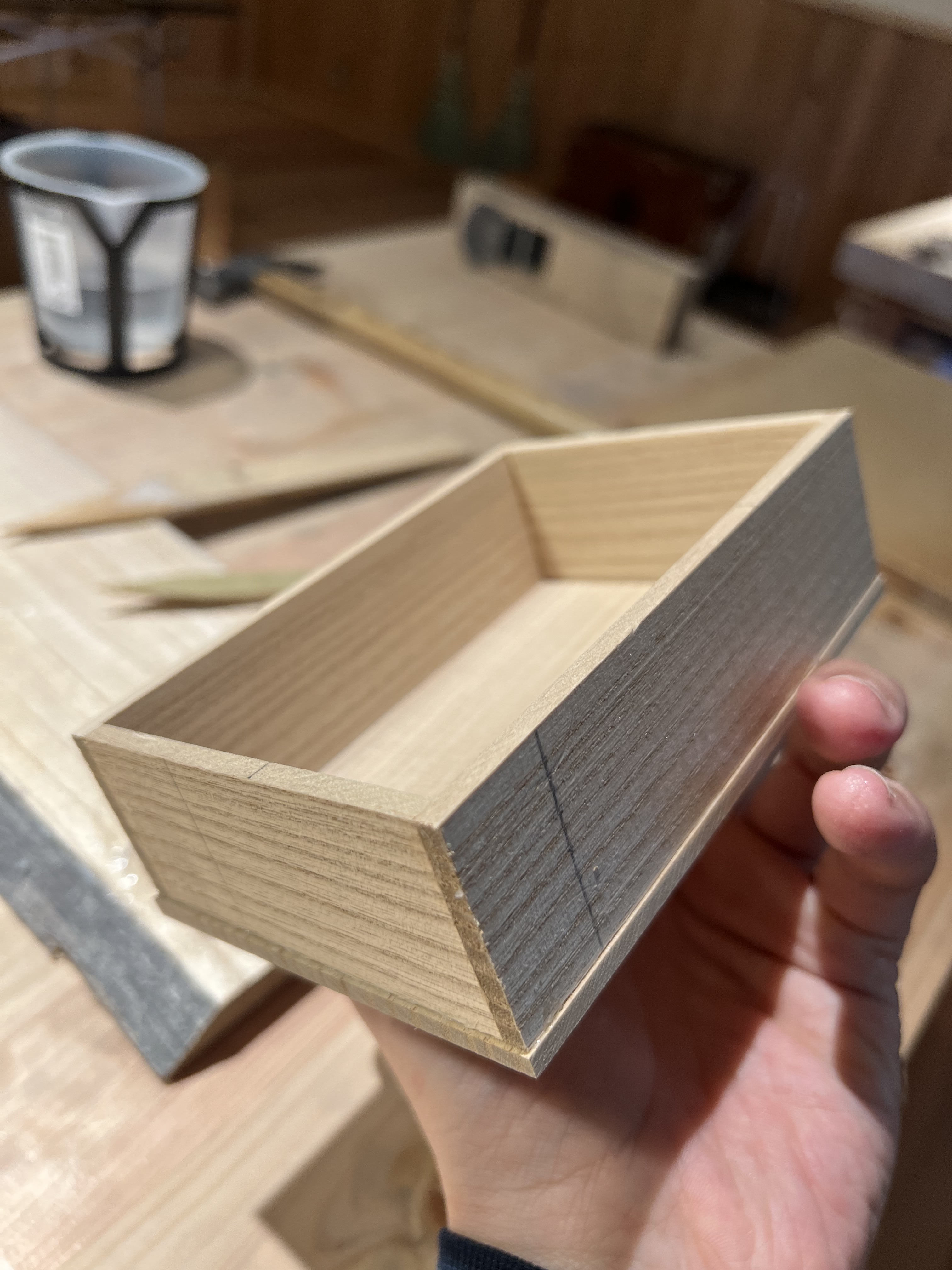

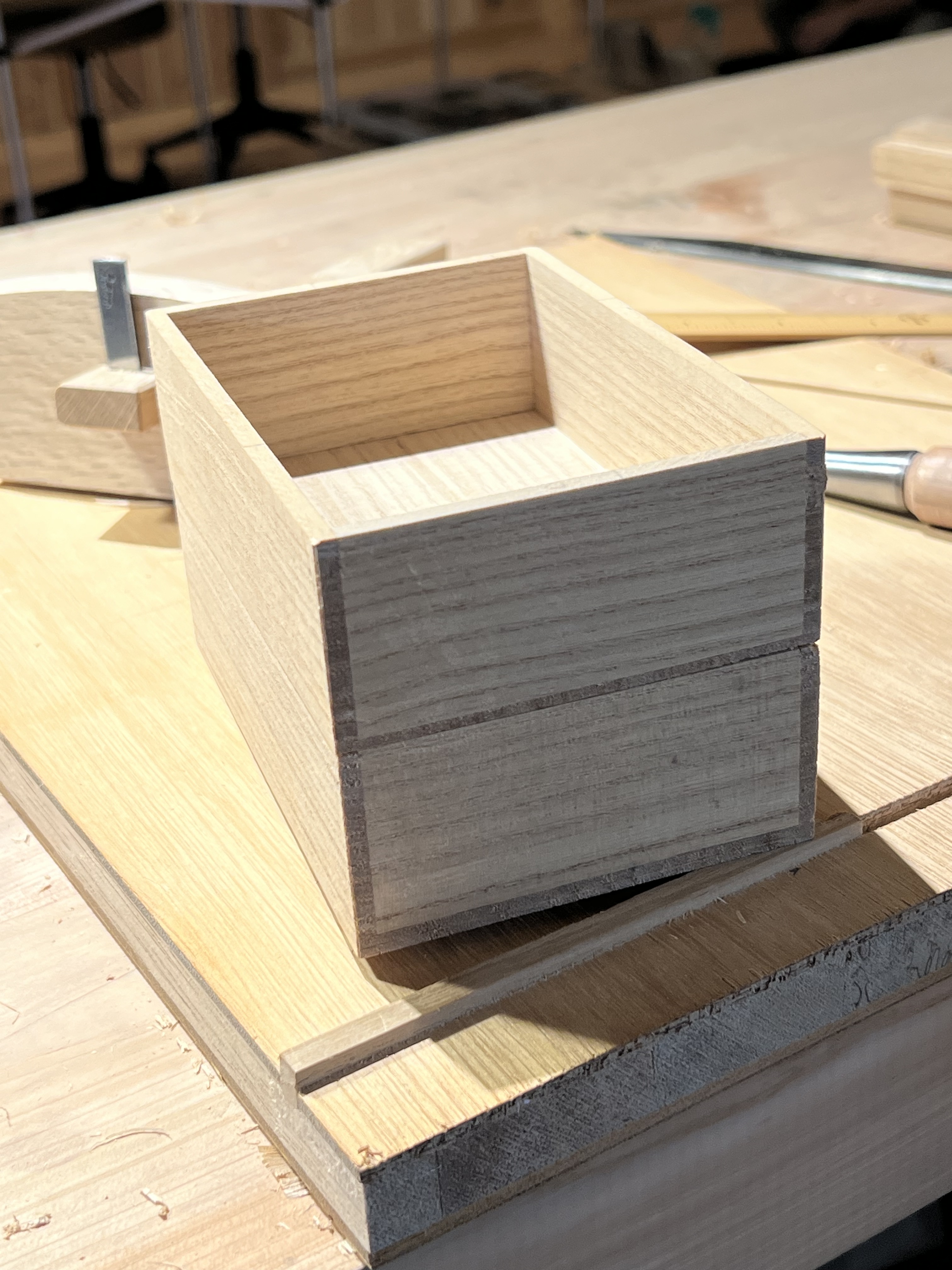

After the tour, we got straight to work on the inside compartment of our bento box. The interior boxes need to be planed flat, squared, glued up, and fastened with wooden pegs.

Today’s class taught me some very important lessons:

Wooden Pegs

Traditionally, pegs made from Utsugi wood were always carved by hand (Figure 1). The shape, length, and type of wood are crucial to help afix the wood joints properly. They are not decorative, though they do add a look signature to sashimono. The holes were also traditionally hand drilled and the pegs must be carved to match the drill bit (also, Figure 1). Once cut, we lightly pan fry the pegs to remove moisture and increase rigidity (Figure 2). The hole must be (hand) drilled at an angle of about 1 – 2 degrees (Figure 3) and the peg subsequently hammered in very gently. The excess is cut off using a flush cut saw (save about 1mm), then hammered flush to the surface, and dabbed with water to help the peg expand into place.

Cutting wooden pegs by hand is rarely done anymore. Why bother? You can probably buy them by the thousands for next to nothing. But what was most illuminating for me was twofold:

(1) Traditions are like fractals, each component is an expression of the whole. That means cutting wooden utsugi pegs is sashimono… This is how it used to be done, and this is how our teacher is teaching us, this is what has gone into developing sashimono as we know it over great periods of time. Is that worth throwing out for convenience and speed? At times, perhaps, but certainly not without learning the way it was traditionally done, and taking the time to do it yourself with discipline, focus, and gratitude for that history.

It’s an honor and a rare opportunity to learn any traditional craft, especially from a teacher.

This is in part why I bow as often as I can to my teachers; at the start of class, after answering my questions, at the end of class, you name it; bowing often isn’t enough for what they’re offering us.

Convenience and efficiency would be the most common argument to bypass carving your own wooden pegs, but I’m not convinced that “quick and convenient” are ever good reasons to do away with tradition. That said, there are times to break the rules, just not before understanding them back to front. I probably have another 9,970 pegs to carve before knowing when to break that rule, but man am I grateful to be learning the traditional way of doing things, and even more grateful for the TIME to do it.

(2) Timelessness. There were times when tasks were done irregardless of the time it took to do them properly, with all of one’s heart, the slow and traditional way. It took Michelangelo over four years to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and even that was rushed by the Pope at the time. Over 500 years later, in such a fast-paced modern world, that “slow” timeline is difficult to justify, especially if your livelihood depends on it. Ironically, however, in this era of artificial intelligence where content creation is equivalent to the 100m dash, I couldn’t be happier to dedicate myself to learning a traditional and slow craft such as sashimono (traditional kintsugi is no exception here, nor is the Art of Tea). I feel unbelievably provided for to simply be able to spend an afternoon carving wooden pegs (or any other traditional aspect of this craft). The space and time for timeless work is a real luxury. I’m savoring it while I can…

Bite of the Blade

One lesson I’m quickly getting a feel for is the bite of a well-sharpened blade, be it the plane blade, chisel edge, hand knife, or miter gauge blade. They’re all razor sharp at this point and each edge communicates differently as it comes into contact with a wood surface. It’s thrilling to feel how clean each blade cuts, or how the most gentle tap of a hammer on the back of a plane body changes the bite significantly. Sharpening wooden peg after peg really taught me how to handle my freshly sharpened hand knife.

A Softer Touch

Matsuda sensei gently emphasizes a softer touch with each tool. It’s slightly counterintuitive, but easing up with such sharp blades usually produces cleaner and more controlled cuts. There’s no need to exert too much pressure or force. When you sharpen your blades well and utilize proper body mechanics, the cutting edge works with you rather than against you. Slowly, slowly, softer and softer.

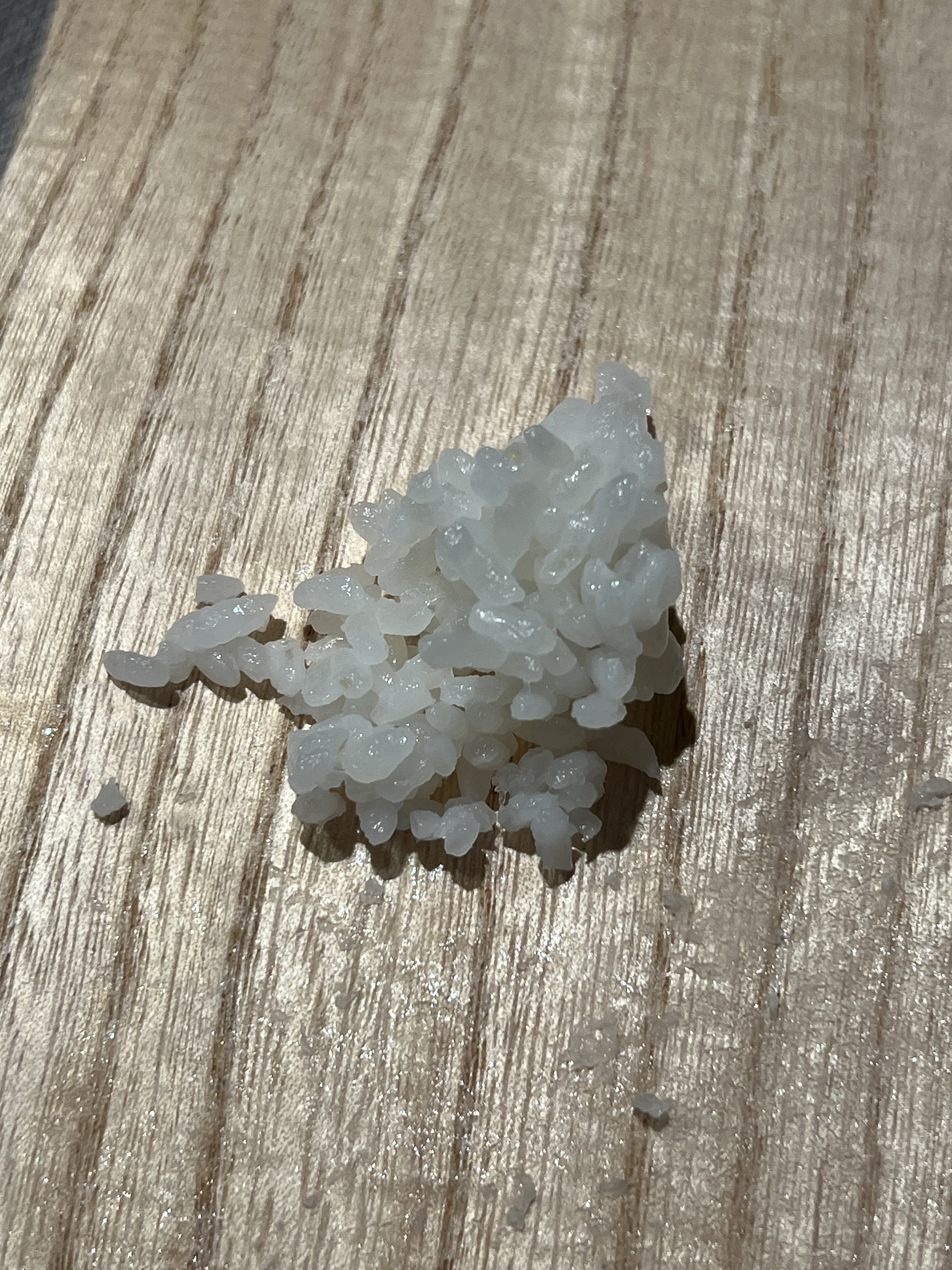

Rice Glue

Believe it or not, you can make natural glue from nothing but cooked rice. All it takes is some strong elbow grease and a bamboo spatula, and voila, 100% natural glue! Food safe, strong, and durable enough. It can’t be compared to modern synthetic glues, of course, but there are Paulownia boxes (with wooden pegs) dozens of years old, strong as the day they were made.

Nowadays, this glue is still used, but is often blended with some modern glue because the one disadvantage of rice glue is that insects will occasionally eat it, wearing down the joints over time.

The moderate strength of rice glue has a surprising advantage. Japan is an earthquake prone country, one of many reasons to store valuables in kiribako—to protect your treasures. When a Paulownia box falls, the joints will often break by absorbing most of the shock, protecting the inner contents. Even when the box itself breaks at the joints, the contents inside are protected. These boxes may look simple at a glance, but as I learn more about making them at each step, I discover how much function, tradition, and wisdom lies within.

Leave a comment