You guessed it—we sharpened all day.

We use an extremely flat metal plate (far left), which is only used to flatten the back of blades

The 1000/400 diamond plate (2nd from left) is for flattening the whetstones. 1000 surface only.

Then we move over to a 1000 grit whetstone (3rd from left) to do the bulk of our work on the bevel

Finally, the burr is removed and the hard steel polished on the 8000 grit whetstone

Embodying the Blade

Each sharpening plate has its own unique sound, weight, texture, feel.

The flat metal steel abrades softly and slowly, truing up the back face of a blade like coursing water on stone over centuries.

The diamond plate is roughest. Think hardened sandpaper. Flattening 10,000 faces, the diamond plates holds strong as an ancient temple beam.

The 1000 grit whetstone stone is soft as mud slurry. The bevel is gently abraded along its supple surface sounding of skates gliding over fresh ice.

And the 8000 whetstone is silent as the dead of night. One would never know a bevel abrades its surface, lest for the feel of silk against steel or of sumi ink on paper.

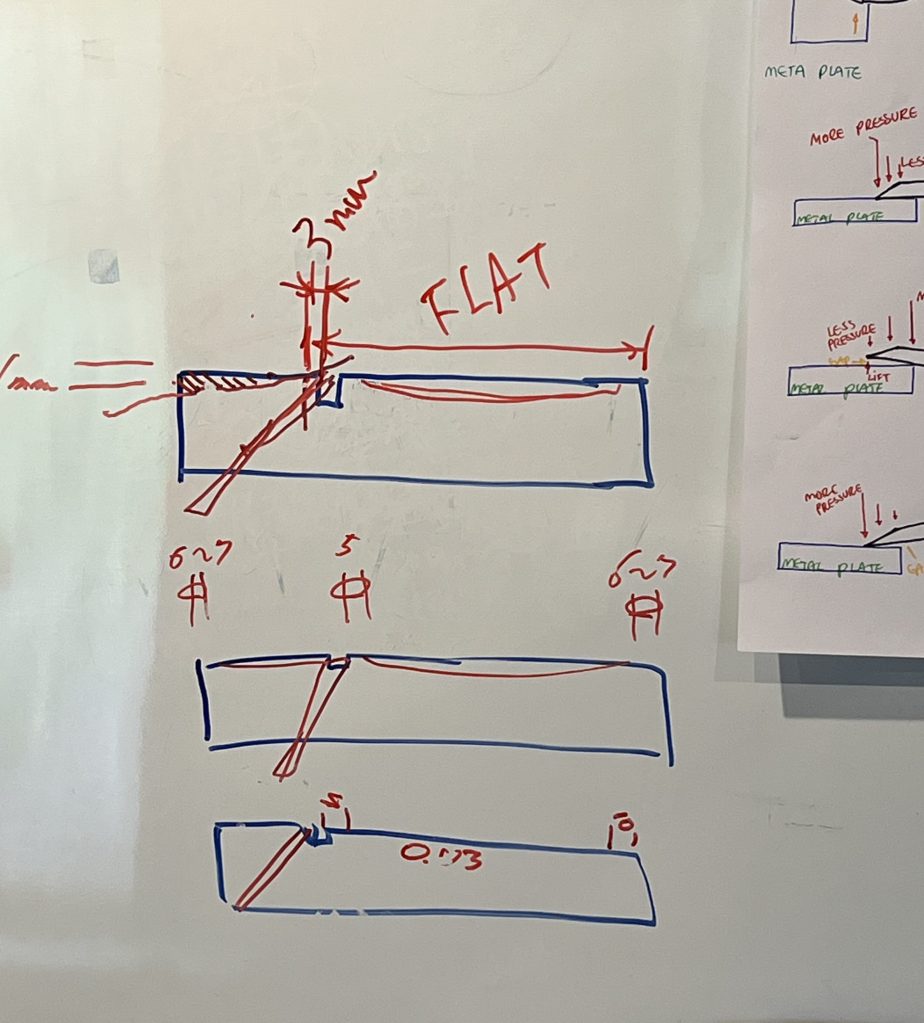

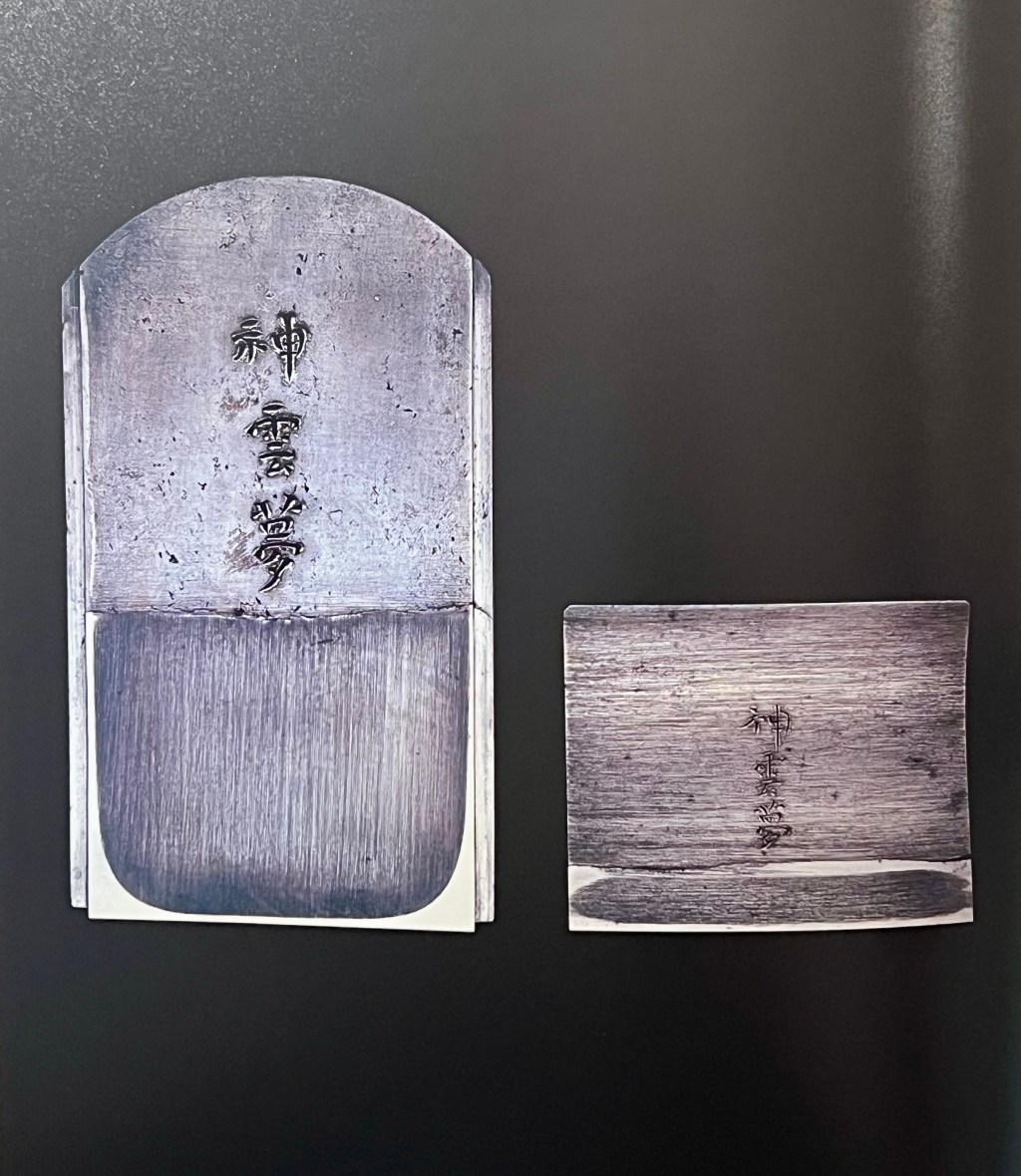

Our teacher told us that blacksmiths and other manufacturers only finish the products to certain percentages. For example, most plane blades are finished to about 80% by the blacksmiths. The rest of the fine-tuning has to be done by the woodworkers themselves. For the plane, that 20% amounts to a lot, and doesn’t even account for the wooden plane body, which also requires plenty of touch up work to house the blade and chipbreaker perfectly. The body of the plane requires hairs-width adjustments on the bottom to not only make sure it is flat but that only certain parts of the bottom make contact with whatever you are planing.

Here, we found out how three different woodworkers adjust the bottom of their planes. Sure enough, they were all slightly different. But no one argued that one way was better than the other. Each craftsperson respected and understood the other. It’s a very personal journey of fine tuning at this point. We created a fusion of all three specifications to aim for.

When I say hairs-width adjustments, I’m not exaggerating. There is a Japanese system of measurement that accounts for it.

| Unit | Reading | Relation | Metric |

| 尺 | Shaku | 1 shaku = 10 sun | 30.03cm |

| 寸 | Sun | 1 sun = 10 bu | 30.03mm |

| 分 | Bu | 1 bu = 10 rin | 3.03mm |

| 厘 | Rin | 1 rin = 1/100 sun | 0.303mm |

| 毛 | Mo | 1 mo = 1/10 rin | hairs width😅 |

Countless hours later (and many “mo” adjustments), we had our blades properly sharpened, the body trued up, the blade + chipbreaker housed as perfectly as we could. To achieve this, we use a hammer as opposed to dial-adjustments found on western style metal planes. The strength of each blow of the hammer can vary anywhere from forceful smashes to infinitesimally small taps.

Today was a lot of fun. Believe it or not, after attempting our first shavings by noon, we then took the afternoon to sharpen one single chisel, our marking gauge blade, and an iron knife. They all required about the same amount of work as the plane blade… That said, the process did go a little faster at that point since we had a little experience under our belts, not to mention these blade surfaces are all smaller and so sharpening naturally takes less time. Not that speed is the goal, but it does take arduous work before we can even begin our Sashimono work.

That said, I should also say that tuning up our Instruments of the Way takes far more time in the beginning when you get them directly off the shelf or from the blacksmith. Maintenance sharpening can take much less time, and since we took the time at the outset to do it right, it will work in our favour in the long run. And in the long run, we slowly slowly develop the relationship to our tools that my teacher spoke of.

Leave a reply to Bernice Marrs Cancel reply